Ratios can be useful when claiming a subset of two well-known components or variables, particularly when the subset (defined by a ratio) provides a new and useful result. However, when the prior art teaches broad ranges for the individual components or variables, it is common for examiners and petitioners to argue obviousness based on overlapping theoretical ranges of the ratio derived from selecting the maximum and/or minimum values for each of the components or variables. The issue with this is approach is that the prior art may not direct a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSA) to the particular selections required to arrive at the claimed ratio. SNF S.A. v. Solenis Technologies is illustrative. IPR2020-01730, Paper 10 at 4 (PTAB April 22, 2021).

In SNF S.A., the challenged claims required a glyoxalated copolymer (G-PAM) obtained by reacting:

[A] 5–40 parts of glyoxal; and

[B] 60–95 parts of a cationic copolymer including:

[b1] ~15–85 wt% of diallyldimethylammonium halide monomer (DADMAC); and

[b2] ~85–15 wt% of acrylamide monomer,

the cationic copolymer having a weight average molecular weight (WAMW) of 120,000 to 1,000,000 Daltons, and

a ratio of the WAMW to the weight % of the DADMAC being greater than 4000 Daltons/weight%.

According to the background of the patent, the patentee found that the ranges of the WAMW and % DADMAC in combination with the claimed ratio thereof improved water drainage during processing and increased the strength of paper or boards treated with the G-PAM.

The petitioner, SNF S.A., argued obviousness based on three different primary references: Wright, Lu, and . The petitioner admitted that none of the cited references disclosed a ratio between WAMW and % DADMAC. To remedy this deficiency, the petitioner presented two arguments.

The petitioner’s first argument was that a POSA would have selected values of the WAMW and % DADMAC disclosed by each of the references to arrive at the ratio required by the claims. Specifically, with respect to the Wright reference, the petitioner argued “the ratio of 150,000 WAMW to 25 wt.% DADMAC, as both taught by Wright ’343, is 6,000 [and] … the ratio of 1,000,000 WAMW to 30 wt.% DADMAC is 33,333.” The petitioner supported this assertion with an expert declaration that similarly stated it would have been “obvious” and “routine” to select molecular weights of 150,000 (an upper endpoint of the preferred range) and to select DADMAC concentrations of 25% and 30% (preferred concentrations).

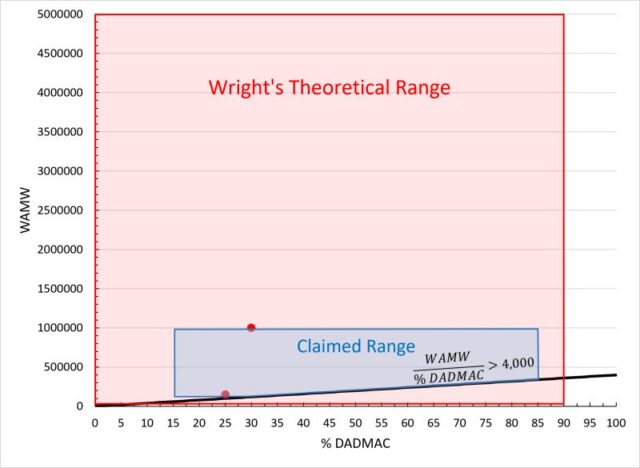

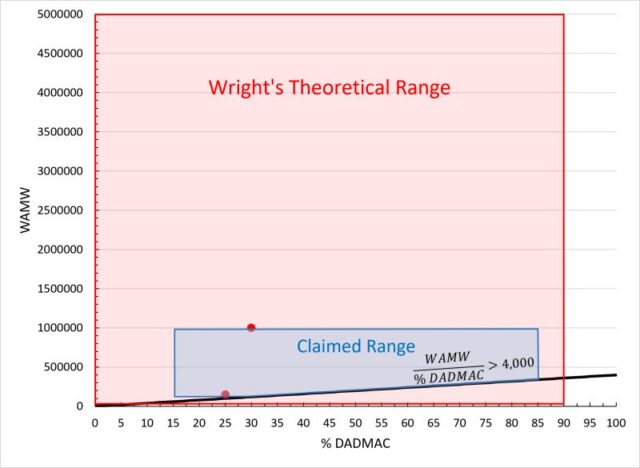

For ease of discussion, the scope covered by the claims (shaded blue box) relative to the scope disclosed by the Wright reference (shaded red box) and the two particular data points of the Wright reference relied on by the petitioner (red dots) are shown graphically below and here:

As shown above, Wright’s broad WAMW range of 30,000 to 5,000,000 and broad % DADMAC range of 0.1–90 wt% cover a WAMW/%DADMAC ratio of 4,000, as they theoretically cover ratios from 333 to 5×107. And although one of the ratios derived by the petitioner (lower red dot) was derived from a preferred amount of DADMAC (25 wt%) and an upper endpoint of a preferred WAMW range (150,000), the Board found:

Petitioner, however, never explains how or why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been led to select the value ‘150,000 WAMW,’ or ‘25 wt.% DADMAC,’ or any of the specific values it uses to calculate the claimed ratio. Nor does Petitioner direct us to any disclosure in the prior art showing an embodiment having the specific values used in Petitioner’s calculations.

…

Absent explanation from Petitioner, it appears that Petitioner picked the specific values it used to calculate a ratio from broad, unrelated ranges of WAMW and % DADMAC disclosed in the prior art simply because they combine to produce a ratio that meets the ratio recited in the claims of the ’320 patent. This suggests Petitioner relied on hindsight in forming its challenges. Metalcraft of Mayville, Inc. v. The Toro Co., 848 F.3d 1358, 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (‘[W]e cannot allow hindsight bias to be the thread that stitches together prior art patches into something that is the claimed invention.’).

This use of hindsight is not excused by the mere fact that the specific values combined to produce the claimed ratio fall within the ranges disclosed in the prior art.

The other two primary references relied on by the petitioner, Lu, and suffered similar defects.

The petitioner’s second argument was that “a POSA would have arrived at the ratio using routine experimentation to optimize result-effective variables, as guided by the art.” The Board also rejected this argument.

First, the Board found that a POSA would not have optimized the ratio itself because “there is no evidence that skilled artisans knew that the claimed ratio of WAMW to % DADMAC was a parameter of any importance or one worth optimizing.” That is, the ratio was not a result-effective variable.

Second, the Board found that there was no persuasive evidence to support a conclusion that independently optimizing WAMW and % DADMAC would result in a polymer having the claimed ratio rather than one of the many ratios falling outside the scope of the claims. Again, the Board emphasized the innumerable combinations of values. But it seemed that the Board was more persuaded by the fact that there was evidence of polymers outside the scope of the claim exhibiting the same properties as those having the claimed ratio such that optimization could equally result in a copolymer having a ratio outside the claim. Ultimately, the Board concluded that the evidence did not support the petitioner’s assertion that independent optimization would lead to the claimed ratio.

For the foregoing reasons, the Board concluded that the petitioner failed to carry its burden and declined to institute the IPR.

Takeaway: When facing an office action or post-grant petition in which a claimed ratio is alleged to be obvious based on the selection or optimization of the components making up the numerator and denominator, you should first determine whether the ratio itself is a result-effective variable. If not, the next step is to determine whether there is an embodiment that discloses values for the numerator and denominator that would result in the claimed ratio. As shown in SNF S.A., the fact that specific values can be combined to produce the claimed ratio is insufficient by itself when there are innumerable combinations of values. If neither of these applies, the final step is to determine whether the prior art teaches a reason to optimize the numerator and denominator in a manner that would result in the claimed ratio.

Judges: C. Crumbley, J. Abraham, D. Cotta