2021年4月16日、CAFCは、発明の優先日時点で実施可能でない引用文献だけを基礎にしたのではその発明を自明とすることはできない、という判断をしました (Raytheon Technologies Corp. v. General Electric Co. (Fed. Cir. Apr. 16, 2021))。

In an anticipation rejection, every element and limitation of the claimed invention must be found in a single prior art reference, arranged as in the claim. However, “it is not enough that the prior art reference . . . includes multiple, distinct teachings that [an ordinary] artisan might somehow combine to achieve the claimed invention.” Net MoneyIN, Inc. v. VeriSign, Inc., 545 F.3d 1359, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Instead, the reference must “clearly and unequivocally disclose the claimed [invention] or direct those skilled in the art to the [invention] without any need for picking, choosing, and combining various disclosures not directly related to each other by the teachings of the cited reference.” Id. (quoting In re Arkley, 455 F.2d 586, 587 (C.C.P.A. 1972)). Although “[s]uch picking and choosing may be entirely proper in the making of a 103, obviousness rejection . . . it has no place in the making of a 102, anticipation rejection.” Arkley, 455 F.2d at 587-88.

This issue is illustrated in the recent Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) case of Ex parte Eckhardt.

Independent claim 16 recited a multilayer pressure-sensitive adhesive assembly comprising a propylheptyl acrylate adhesive copolymer layer and a second acrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive foam layer. The propylheptyl acrylate adhesive copolymer layer comprised (a) 50 to 99.5 weight percent of 2-propylheptyl acrylate as a first monomer, (b) 1.0 to 50 weight percent of a second non-polar monomer, (c) 0.1 to 15 weight percent of a third polar acrylate monomer, and (d) a tackifying resin in an amount of 3 to 100 parts per 100 parts of the copolymer. Independent claims 37 and 38 recited similar multilayer pressure-sensitive assemblies, but with somewhat different components (d), and different scope of components (a), (b) and (c).

The examiner rejected independent claims 16, 37 and 38 as anticipated by a single reference, Bartholomew. In response, the applicant argued that “[t]he cited reference provides a great multiplicity of possible combinations and no direction that would lead one of skill in the art to the claimed invention.” For component (a), the applicant explained that Bartholomew listed “2-propylheptyl acrylate as one of 10 options.” For the specific components (b) and (c) recited in claims 37 and 38, the applicant explained that component (b) was one of eight options listed in Bartholomew, and component (c) was one of ten listed options. For component (d), Bartholomew described a tackifying resin as optional. Based on this, the applicant argued that “the number of possible combinations presented by these passages in Bartholomew is 10 x 8 x 10 x 2 = 1600.” The applicant argued against anticipation because “one of ordinary skill in the art would be required to pick items from at least 1600 types of polymer to arrive at the claimed invention.”

The Board agreed with the applicant, finding that the anticipation rejections “rely upon picking and choosing from various lists in Bartholomew,” and that “[a] preponderance of the evidence supports Appellant’s position that Bartholomew’s disclosure is insufficient to establish anticipation of the compositional components of independent claims 16, 37, and 38.”

Additionally, the Board noted that although the ranges of amounts of components (a), (b) and (c) in Bartholomew overlapped the claimed ranges, “the Examiner has not adequately explained how Bartholomew anticipates the claims” in view of Titanium Metals Corp. v. Banner, 778 F.2d 775 (Fed. Cir. 1985).

Accordingly, the Board reversed the anticipation rejections. However, the Board entered a new ground of rejection, finding the claims obvious over Bartholomew. Specifically, the Board found that the selection of the claimed components, in the claimed amounts, would have been obvious from Bartholomew. The Board was not persuaded by the applicant’s argument of unexpected results, particularly with respect to a showing of criticality and whether the unexpected results were commensurate in scope with the claims.

Takeaway: When an examiner rejects a claim as anticipated based on several selections from lists disclosed in a prior art reference, a strong case can be made against anticipation. After overcoming the anticipation rejection, however, the question of obviousness usually remains. To rebut the case of obviousness, strong evidence of unexpected results often is necessary.

Judges: Gaudette, Hastings, Ren

Ex parte Yim, is a recent decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) addressing whether claimed properties were inherent in prior art compositions.

In Ex parte Yim, the claim at issue was directed to a resin. However, the resin was not defined by structure or composition. Instead, only properties of the resin were recited in the claim: (a) content of water-soluble fraction, (b) absorbency against pressure property, and (c) water-soluble fraction shear index property. Independent claim 16 is reproduced in part below:

16. A water-absorbing resin, in which

[a] a content of a water-soluble fraction is 15 wt% or less based on the total weight of the resin,

[b] an absorbency against pressure at 0.3 psi with respect to a saline solution including sodium chloride at 0.9 wt% is 25 g/g or more, and

[c] a water-soluble fraction shear index A/B represented by the following Expression 1 is in a range of 0.1 x 10-5 (s) to 10 x 10-5 (s)….

In rejecting the claim, the examiner relied on a single prior art reference that disclosed a water-absorbing resin but did not disclose the properties recited in the claim. Both the prior art reference and the application on appeal disclosed forming water-absorbing polymers by polymerizing and crosslinking an acrylic acid monomer. The examiner asserted that, in view of the similarities in starting materials and processing steps used in the prior art reference and the application on appeal, the properties in the claim were inherent in the water-soluble resins of the prior art reference.

The examiner further asserted that, even if applicant could demonstrate that none of the water-soluble resins exemplified in the prior art reference had the claimed properties, it would have been obvious to tune the reactions in the prior art references to optimize absorbance/solubility characteristics.

The examiner’s inherency arguments turned, particularly, on the examiner’s determination that the prior art reference used two internal crosslinkers to crosslink an acrylic acid, which was the same or similar to the method disclosed in the application on appeal. Applicant countered by arguing, inter alia, that the steps of the prior art method were different such that the two internal crosslinkers were reacted together before being added to acrylic acid, which could not be said to necessarily result in the claimed properties.

The PTAB found that the examiner had made a good argument that the processes of the prior art reference would result in the claimed properties, such that it became applicant’s burden to show that the exemplified resins did not possess the claimed properties. The PTAB also noted that applicant failed to present arguments rebutting the examiner’s fallback assertion that optimizing the properties of the prior art resin would have been a mere matter of routine experimentation to a skilled artisan. Thus, the examiner’s rejection was affirmed.

Takeaway: Parameter or property claims can be valuable in a patent directed to a material or chemical composition. By keeping strict compositional or structural limitations out of a claim, materials or compositions not contemplated at the time of filing may be encompassed by the claim. Further, if claimed parameters/properties are not explicitly disclosed in the prior art, it can be difficult for a third party to confidently analyze the validity of the claim. However, these advantages in a patent claim can be challenges during examination. While some parameter/property claims “sail through” examination, Ex parte Yim shows that an applicant should be prepared to reproduce prior art examples and provide evidence to rebut assertions of routine optimization to obtain allowance.

Judges: Timm, Smith, Range

In February, the Federal Circuit issued a decision in Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. v. Torrent Pharmaceuticals Ltd. concerning the obviousness of a chemical compound. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the court’s decision was the framework that they used in making their decision.

The case arose in ANDA litigation, with Takeda alleging that Torrent would infringe Takeda’s Orange Book-listed patent claiming certain alogliptin benzoates. Torrent defended by alleging obviousness – both statutory obviousness (35 U.S.C. 103) and non-statutory obviousness-type double patenting – and in all cases relied on the obvious modification of a “lead compound” to produce Takeda’s claimed compounds.

In Takeda, central to the court’s ultimate decision-making process was determining whether there was a “reasonable expectation of success” in making Torrent’s suggested modifications. But in essentially answering this question before it was asked, the court prefaced its discussion with the following statement:

Relevant to ‘the assessment of [reasonable] expectation of success’ in all three of [Torrent’s] invalidity theories … is the undisputed factual finding that ‘in the relevant art of pharmaceutical development, very small changes in molecular structure can have dramatic effects on the properties of the molecule,’ …. Indeed, ‘the more distantly related two chemical structures are, the less probable it will be that they have the same biological effect.’ … Against this backdrop, we turn to the details of Appellants’ invalidity theories.

As one might guess just from reading this opening decisional framework, the court found in favor of Takeda, holding that a skilled artisan would not have been motivated to modify Torrent’s lead compound with a reasonable expectation of success.

Takeaway: Does the Takeda case provide us with a roadmap to nonobviousness? Perhaps. In Takeda patentee used expert testimony, buttressed by a publication, to establish the unpredictability of chemical structural changes vis-à-vis functionality in the relevant pharmaceutical art. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, the Federal Circuit found it very easy to affirm the validity of Takeda’s claims and deny Torrent’s allegations of obviousness. Using this strategy during prosecution should yield the same results, with the advantage of an “adversary” (i.e., the Examiner) who lacks the resources of a pharmaceutical litigant.

Judges: Dyk, Mayer, Chen

A conclusion of obviousness requires that a skilled artisan would have had a reason to combine the teachings of the prior art references to achieve the claimed invention, and that the skilled artisan would have had a reasonable expectation of success from doing so.

The reasonable expectation of success requirement can be difficult to challenge during prosecution because the reply is consistently that “only a reasonable expectation of success, not absolute predictability, is necessary for a conclusion of obviousness.” In re Longi, 759 F.2d 887, 897 (Fed. Cir. 1985). This seemingly insurmountable conclusion is compounded by a lack of bright-line rules defining when a reasonable expectation of success exists. However, Ex parte Saerens provides a nice example of facts resulting in a conclusion that a skilled artisan would not have had a reasonable expectation of success. Appeal No. 2020-005386 (PTAB Feb. 25, 2021) (non-precedential).

The claims in Saerens were drawn to a method for fermenting cocoa beans with at least one Pichia kluyveri yeast strain, where the fermented cocoa beans exhibited particular ratios of isobutyl acetate/isobutanol and isoamyl acetate/isoamyl alcohol.

The Examiner relied on a primary reference for its disclosure of adding pectinolytic yeast during cocoa bean fermentation and cited a secondary reference for evidence that certain strains of Pichia kluyveri are pectinolytic. According to the Examiner, a skilled artisan would have had a reason to select Pichia kluyveri from the secondary reference for use as the pectinolytic yeast in the primary reference.

The Appellant disagreed because the secondary reference “focused on examination of pectinolytic activity on a coffee substrate, not cocoa” and there was no evidence the Pichia kluyveri would have exhibited similar activity on all pectin-containing substrates, or would otherwise have been useful for cocoa bean fermentation. In response, the Examiner argued that “pectinolytic activity is universal,” and predictably stated that “Appellants are reminded that only a ‘reasonable expectation of success’, not an ‘absolute success’ would have been required in an obviousness rejection.” Examiner’s Answer at 15.

Reversing the Examiner’s rejection, the Board held that “the prior art must give some indication of which parameters were critical or which of many possible choices is likely to be successful.” Here, however, the secondary reference relied on by the Examiner showed significantly different Pichia kluyveri activity when cultured on yeast polygalacturonic acid medium vs. coffee broth. Consequently, the evidence of record showed that Pichia kluyveri activity would have been considered substrate-specific in complete contradiction to the Examiner’s unsubstantiated finding that “pectinolytic activity is universal,” irrespective of whether the substrate is coffee or cocoa.

Accordingly, the Board found that a skilled artisan would not have been guided by the secondary reference to substitute Pichia kluyveri for any of the yeasts in the primary reference, and reversed the Examiner’s rejection.

Takeaway: It can be difficult to persuade an Examiner who has already concluded there would have been a reasonable expectation of success even when the subject matter claimed is unpredictable, as with the chemical and biological arts. This is illustrated in Saerens, where the Examiner maintained the obviousness rejection despite the experimental data in the secondary reference itself contradicting his conclusion of “universal activity.” Nevertheless, it is important to present any experimental data, technical publications, and/or expert testimony that shows unpredictability as these will be more persuasive than mere attorney argument. In the event that an Examiner is not persuaded by such evidence, the evidence can serve as a basis for reversal in a formal appeal.

Judges: C. Timm, G. Best, J. Snay

Chemical compounds in patent claims often include variables representing different possible substituent groups. For example, a chemical formula may include a variable R1 representing a hydrogen atom or an alkyl group, a variable R2 representing an alkenyl group, and a variable X representing a halogen atom. This notation allows for a compact representation of many different specific compounds (species) within a generic formula (genus).

When evaluating a genus of chemical compounds for obviousness, U.S. examiners often find a disclosed genus of chemical compounds sharing species with the claimed genus. The question then is whether the disclosed genus of chemical compounds is sufficient to render obvious the claimed genus of compounds. This issue is illustrated in the recent Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) case of Ex parte Alig.

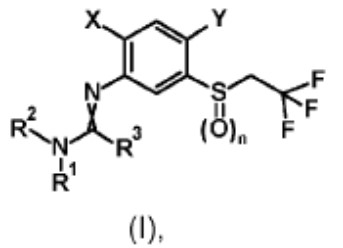

Independent claim 1 recited a method for controlling animal pests with an N-arylamidine substituted trifluoroethyl sulfoxide derivative of formula (I):

where:

n represents the number 1,

X represents fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine,

Y represents (C1-C4)-alkyl or (C1-C4)-haloalkyl,

R2 represents hydrogen, (C1-C4)-alkyl or (C1-C4)-haloalkyl, and

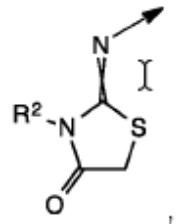

R1 and R3 together with the atoms to which they are attached represent the group

where the arrow points to the remainder of the molecule.

The examiner rejected claim 1 on the ground of non-statutory obviousness-type double patenting over claims 1-20 of U.S. Patent No. 9,642,363 (“the ‘363 patent”) in view of WO 2007/131680. As articulated by the Board, “[t]he Examiner’s position, essentially, [was] that the pending claims would have been obvious over the reference claims because the reference claims disclose a genus of compounds that encompasses the compounds recited in the pending claims.”

The applicant explained that to arrive at the compounds in the pending claims, a person of ordinary skill in the art would need to make several specific choices to narrow the genus recited in the reference claims. For example, the person would need to choose the specific ring structure formed by R1 and R3 in pending claim 1 from among 14 ring systems recited in claim 1 of the ‘363 patent and 16 groups recited in claim 8 of the ‘363 patent. Additionally, the person would need to choose fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine for the variable X in pending claim 1, from among 41 substituents (many of which could contain further substitutions) in the claims of the ‘363 patent. The person also would need to choose (C1-C4)-alkyl or (C1-C4)-haloalkyl for the variable Y in pending claim 1, from among 41 substituents (many of which could contain further substitutions) in the claims of the ‘363 patent. The applicant argued that pending claim 1 was not obvious because the “claims of the ‘363 patent provide no teaching whatsoever that would suggest the specific choices that would lead to the claimed compounds.”

The Board agreed with the applicant. The Board explained that “[t]he fact that the pending claims recite compounds encompassed within the genus disclosed in the prior art is not, by itself, sufficient to establish a prima facie case of obviousness” (citing In re Baird, 16 F.3d 380 (Fed. Cir. 1994) and In re Jones, 958 F.2d 347 (Fed. Cir. 1992)). The Board noted that “[i]n both Baird and Jones, our reviewing court reversed rejections similar to the present rejection, in which the rejected compounds were encompassed by large genera that included millions of compounds, but the prior art did not suggest selecting from those genera the particular compound, or subgenus of compounds, recited in the claims at issue.”

The Board found that the examiner did not “provid[e] a sufficient evidentiary basis explaining why, out of the enormous number of possibilities encompassed within the genus described in the ‘363 patent, a skilled artisan would have made the particular set of selections and modifications that would be required to arrive at the compounds recited in the pending claims.” The Board concluded that “[t]he mere fact that one might arrive at Appellant’s claimed compounds by a hindsight-guided selection of appropriate substituents from the large genus disclosed in the reference claims does not persuade us that the pending claims would have been obvious to a skilled artisan.” Thus, the Board reversed the double patenting rejection.

Takeaway: When claims recite a sub-genus of chemical compounds, and the examiner rejects the claims as obvious over a broader genus of compounds, it is important to analyze the selections necessary to arrive at the sub-genus. If the applied references do not provide guidance for making such selections, then a strong argument can be made against obviousness.

Judges: Fredman, Cotta, Hardman

2021年2月24日、CAFCは、組成物の一成分が他成分の副生物である場合に、置換理論 (substitution theory) を適用して行われた自明性の認定を肯定するnon-precedential判決を出しました (Daikin Industries Ltd. v. The Chemours Company FC, LLC (Fed. Cir. Feb. 24, 2021)) 。

In January of this year we reported on the Federal Circuit decision Donner Technology, LLC v. Pro Stage Gear, LLC, (link here) where the court clarified the “reasonably pertinent” test used to define the scope of analogous prior art (i.e., whether a reference outside the field of the inventor’s endeavor is “reasonably pertinent” to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved). In Donner the Federal Circuit explained that the problem to which the allegedly non-analogous reference relates must be identified and reviewed from the perspective of one of ordinary skill in the art who is considering turning to art outside their field of endeavor, and the question that must be answered is whether this person “would reasonably have consulted” the reference in solving the relevant problem.

On March 2, 2021, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) issued a decision in Ex parte Brophy (Appeal No. 2021-001800) reversing the Examiner’s rejection of claims to a salt substitute that relied on a reference requiring the use of an ingredient not safe for food. While two of the cited references used in the Examiner’s rejection were related to consumable salt compositions which included all the components recited in the claims, both references failed to describe the physical forms of the claimed salt substitute (solution and crystalline). In view of this omission, the Examiner cited a third reference describing an evaporative salt crystallization technique described as providing free-flowing salt crystals suitable for use in membrane electrolysis cells and in chlorine production using water, the salt to be crystallized, and a water-soluble acrylic polymer.

Appellants argued that the third reference was non-analogous with regard to its field of endeavor (salts for membrane electrolysis cells and for use in chlorine production), both in general and as evidenced by its use of acrylic acid, and provided the Examiner with a reference showing that a commercial polymer taught by the third reference was hazardous to humans. The Board agreed with Appellants and reversed the Examiner, and following the Federal Circuit’s guidance in Donner held that the Examiner failed to “address the underlying question why one of ordinary skill in the art would have looked to [the third reference’s] method for producing electrolysis salts to produce salt seasoning compositions intended for food.”

Takeaway: Non-analogous art arguments, while historically difficult, seem to be gaining more traction recently. Both the Federal Circuit’s and the Board’s recent guidance should be used during prosecution to establish all the elements of the argument, should appeal become necessary.

Judges: B. Franklin, J. Housel, and J. Snay

In Ex parte Gomez (Appeal 2020-001462), the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) considered an Examiner’s obviousness rejection based on an allegedly overlapping range and, alternatively, optimization of a result-effective variable. The Board found neither of the Examiner’s two rationales were persuasive.

The sole independent claim 19 illustrated the claimed subject matter on appeal and was drawn to a method of improving the scratch resistance of a glass. The claimed method included, among other steps, a step of “forming a porous silica-rich layer on the surface of the glass, wherein the silica-rich layer extends from the surface to a depth of greater than or equal to 100 nm to less than or equal to 600 nm into the glass.”

The Examiner rejected claim 19 as obvious over Amin. The Examiner found Amin disclosed the formation of a porous silica-rich layer on a surface of a glass by treating the surface with an acid to improve the scratch resistance of the glass. The Examiner noted Amin disclosed the preferred depth of the silica-rich layer was less than 50 nm, which was outside the claimed depth range. However, the Examiner contended the claimed depth of the silica-rich layer would still have been obvious over Amin under two rationales.

First, the Examiner noted Amin disclosed that the surface of the glass had a root mean square (RMS) roughness of 50-5000 nm. While acknowledging “RMS roughness is not directly equivalent to the depth,” the Examiner believed “given that it is the root mean square of the peak-to-valley heights (i.e. root mean square of the depth across the surface) it is apparent that a RMS roughness of 50–5000 nm overlaps [the recited depth range].”

Second, the Examiner found the depth of the silica-rich layer was a result-effective variable because Amin disclosed that the silica-rich layer was selected “based on the desired balancing between the improved adhesion of the subsequent layer and a depth whereby the mechanical properties are not affected.” The Examiner then concluded it would have been obvious to optimize the depth and arrive at the claimed range “to obtain the desired chemical and mechanical properties.”

The Board found Amin’s disclosure of the RMS roughness of 50-5000 nm was related to an alternative embodiment of Amin’s invention that involved forming a glass article having a textured or patterned surface disposed between a chemically strengthened layer and an exterior amphiphobic layer. The Board pointed out the Examiner did not provide technical reasoning supported by objective evidence to prove that RMS roughness corresponded to, or was equivalent to, the depth of a silica-rich layer into a glass. Because the Examiner’s allegedly overlapping range disclosed in Amin appeared to relate to a variable irrelevant to the claimed depth of silica-rich layer, the Board concluded the Examiner’s assertion of overlap appeared to be based on speculation, which did not constitute a sufficient basis for establishing prima facie obviousness.

In addressing the Examiner’s allegation of optimization of a result-effective variable, the Board found that Amin described conducting an acid treatment to remove chemically exchanged (potassium) ions from the surface of a glass to a depth typically of ≤ 50 nm, “whereby the mechanical performance of the chemically strengthened glass (for example, strength, scratch resistance, impact damage resistance) is not affected.” Amin further disclosed the depth was preferably 5-15 nm and described a specific example in which the depth was only 10 nm. The Board noted these disclosed depth values were “all far below” the recited depth range and concluded “[one] of ordinary skill in the art would have understood this disclosure to implicitly indicate that removing chemically exchanged ions to a depth greater than 50 nm may adversely affect the mechanical performance of the glass.” The Board did not find the Examiner provided sound technical reasoning supported by objective evidence to establish that a skilled artisan would have disregarded Amin’s explicit disclosure of a typical depth of ≤ 50 nm and implicit disclosure that removing ions to a greater depth might adversely affect the mechanical performance of the glass.

Citing In re Sebek, the Board emphasized that “[when] the prior art disclosure suggests the outer limits of the range of suitable values, and that the optimum resides within that range, and where there are indications elsewhere that in fact the optimum should be sought within that range, the determination of optimum values outside that range may not be obvious.” In Gomez, the claimed depth range was outside an optimum range of ≤ 50 nm disclosed in Amin and Amin taught in multiple places that the depth should be within the optimum range. In other words, Amin appeared to teach away from the claimed depth range. Therefore, the Board also rejected the Examiner’s optimization rationale.

Because the Examiner did not provide a sufficient factual basis to support his conclusion that the claimed depth of the silica-rich layer would have been obvious over Amin, the Board reversed the rejection.

Takeaway: Claiming a range is particularly common in chemical arts. If a claimed range does not overlap a prior art range, examiners will sometimes argue the parameter of the range is a result-effective variable that could be optimized to reach the claimed range. As illustrated by Gomez (see also Nonobviousness: PTAB Rejects Examiner’s Optimization by Routine Experimentation Rationale), even if the parameter passes the muster to be a result-effective variable, the optimization rationale will not stand if the prior art implicitly teaches away from the claimed range by disclosing a non-overlapping optimum range and encouraging one to seek a value within the optimum range.

Judges: R. H. Delmendo, M. P. Colaianni, and J. E. Inglese

Ex parte Whalen, is a 2008 decision of the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI) that is listed among the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s (PTAB) precedential decisions. Ex parte Whalen, is indicated by the PTAB to be precedential as to “Anticipation – 35 U.S.C. § 102… Inherency… evidence and reasoning” and “Obviousness – 35 U.S.C. § 103… Rationales… optimizing a variable.”

According to the PTAB’s Standard Operating Procedure, “[a] precedential decision is binding Board authority in subsequent matter involving similar facts or issues.”

In Ex parte Whalen, the BPAI considered whether an examiner met his burden in asserting inherency, or alternatively routine optimization, of a claimed viscosity that was not explicitly disclosed in the prior art.

Independent claim 1 was identified as a representative claim:

A composition capable of embolizing an aneurysm at a vascular site comprising:

(a) a biocompatible polymer;

(b) a biocompatible contrast agent wherein a sufficient amount of said contrast agent is employed in said composition to effect visualization in vivo; and

(c) a biocompatible solvent which solubilizes said biocompatible polymer

wherein a sufficient amount of said polymer are [sic] employed in said composition such that, upon delivery to a vascular site, a polymer precipitate forms which embolizes said vascular site; and

further wherein the biocompatible polymer has a molecular weight sufficient to impart to the composition a viscosity of at least about 150 cSt at 40° C.

The claim was rejected as anticipated or obvious over several prior art references. All of the cited prior art references disclosed combinations of components (a), (b), and (c) in compositions for embolizing an aneurysm at a vascular site, but none explicitly disclosed a composition having “a molecular weight sufficient to impart to the composition a viscosity of at least about 150 cSt at 40° C.” The examiner argued that the prior art compositions inherently possessed the claimed viscosity or, alternatively, it would have been obvious to a skilled artisan to “optimize” the prior art compositions by increasing their viscosity to the level recited in the claims.

It was undisputed that the prior art disclosed compositions including components (a), (b), and (c) in amounts overlapping those in the specification and claims of the application on appeal. However, the only disclosure in the prior art of viscosity was of a preferred composition having a viscosity much lower than the viscosity specified in claim 1. The BPAI found that the examiner had not met his burden in establishing inherency. The BPAI stated that, even if some of the compositions encompassed by the prior art’s broad disclosure might have the claimed viscosity, “that possibility is not adequate to support a finding of inherent anticipation.” The BPAI noted that the examiner did not provide evidence or scientific reasoning to show that any specific composition disclosed in the prior art was within the scope of claim 1.

The examiner’s obviousness position rested on the assertion that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to optimize the viscosity of the prior art composition to achieve “the safest clinical outcome and avoiding transvenous passage.” The BPAI noted that the prior art disclosed “adjustment of the viscosity of the composition as necessary for catheter delivery can be readily achieved by mere adjustment of the molecular weight of the copolymer composition.” However, the prior art also disclosed that low viscosity was a desired property in embolic compositions and, as noted above, the only disclosed viscosity in the prior art was much lower than that of claim 1.

Taking the foregoing facts into consideration, and mindful of the Supreme Court’s (then) recent command of “flexibility” in the obviousness inquiry (KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007)), the BPAI nonetheless concluded that the examiner had not met his burden. Particularly:

… when the prior art teaches away from the claimed solution as presented here… obviousness cannot be proven merely by showing that a known composition could have been modified by routine experimentation or solely on the expectation of success; it must be shown that those of ordinary skill in the art would have had some apparent reason to modify the known composition in a way that would result in the claimed composition.

That is, the examiner was required but failed to provide an “explanation based on scientific reasoning” that would support the conclusion that a skilled artisan would have considered it obvious to optimize the prior art compositions by increasing their viscosity to the level recited in the claims.

Ex parte Whalen was decided by an expanded five-judge panel, instead of the usual three-judge panel. The Chief Administrative Patent Judge was one of the deciding judges. According to the PTAB’s Standard Operating Procedure, “[a]n expanded panel is not favored and ordinarily will not be used… [a]n expanded panel may be used, where appropriate, to secure and maintain uniformity of the Board’s decisions…”

Takeaway: One of the challenges of prosecuting composition claims (combinations of known components) is the seeming ease with which an examiner can assert that a property not explicitly disclosed in the prior art is inherent and/or would have been readily achieved by a skilled artisan as a matter of routine optimization. Of course, the burden-shifting framework for examination of claims reciting properties is reasonable; however, there remains some burden on the examiner. Rejections based on inherency or routine optimization require that the examiner provide “scientific reasoning” consistent with the overall teaching of the prior art. Conclusory or thinly reasoned assertions of inherency or routine optimization thus provide an avenue for challenge.

Judges: Fleming, Lane, Grimes, Lebovitz, Prats