Mylan Pharm. v. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., No. 2021-2121 (Fed. Cir. Sep. 29, 2022), is a recent decision of the Federal Circuit considering, inter alia, whether a prior art disclosure of a genus of salts was sufficient to anticipate or render obvious a single salt species.

In an Inter Partes Review proceeding before the PTAB, Mylan asserted that claims of a Merck patent were anticipated by or obvious over a prior Merck patent publication, Edmondson. The PTAB concluded that Mylan failed to prove unpatentability, and Mylan appealed. The claims of the Merck patent at issue were directed to sitagliptin dihydrogenphosphate (DHP). Exemplary claims include claims 1, 2, and 4:

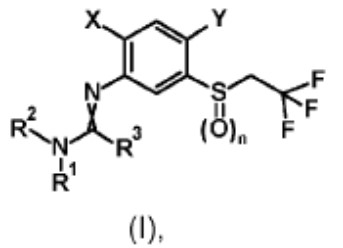

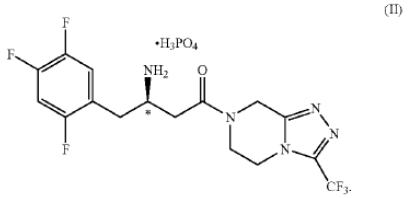

1. A dihydrogenphosphate salt of a 4-oxo-4-[3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6-dihydro [1,2,4]tria-zolo[4,3-a]pyrazin-7(8H)-yl]-1-(2,4,5-tri-fluorophenyl)butan-2-amine… or a hydrate thereof.

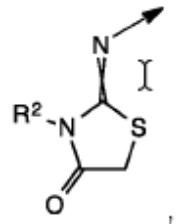

2. The salt of claim 1 of structural formula II having the (R)-configuration at the chiral center marked with an *

.

.

4. The salt of claim 2 characterized in being a crystalline monohydrate.

Edmondson disclosed sitagliptin in a list of 33 compounds. Edmondson further disclosed acids forming pharmaceutically acceptable salts including phosphoric acid in a list of eight preferred acids. Mylan argued that this was sufficient to anticipate claim 1, relying on the reasoning of In re Petering, 301 F.2d 676, 681 (C.C.P.A. 1962) (prior art may be deemed to disclose each member of prior art genus when skilled artisan can “at once envisage each member of this limited class”).

Merck countered that the combined list of 33 compounds and eight preferred salts, taking into account various stoichiometric possibilities, encompassed 957 salts, which was not sufficient for a skilled artisan to “at once envisage” the salt of claim 1.

The Federal Circuit agreed with Merck that Edmondson did not “expressly disclose a 1:1 sitagliptin DHP salt.” The Federal Circuit credited expert testimony (including testimony of Mylan’s own expert) that Edmondson did not direct a skilled artisan to sitagliptin among the list of 33 compounds and did not single out phosphoric acid or any phosphate salt among the enumerated salts. The Federal Circuit noted particularly that the 957 salts of Edmondson was “a far cry from the 20 compounds ‘envisaged’ by the narrow genus in Petering.”

As to obviousness, interestingly, Merck was able to eliminate Edmondson as a reference as to claims 1 and 2 by proving prior invention and relying on the obviousness exception for commonly owned prior art of pre-AIA 35 USC 103(c). However, this approach was not effective as to claim 4, which was limited to a crystalline monohydrate of the (R)-configuration of 1:1 sitagliptin DHP.

As to claim 4, Mylan relied on Edmondson’s indication that the described salts may exist in more than one crystal structure and in the form of hydrates. Mylan further relied on the disclosure in a secondary reference of the pharmaceutical importance and prevalence of crystalline hydrates of pharmaceutical compounds.

The CAFC agreed with the PTAB and Merck that the general teachings of the secondary reference would not have led a skilled artisan to prepare a crystalline monohydrate of the (R)-configuration of 1:1 sitagliptin DHP based on the teachings of Edmondson with a reasonable expectation of success, noting the unpredictability of hydrate formation and function for specific compounds.

The Federal Circuit briefly noted the PTAB’s consideration of Merck’s evidence of unexpected results, but also noted that “there is no need to reach objective indicia of nonobviousness where the petitioner has not made a showing necessary to prevail on threshold obviousness issues.”

Takeaway: During examination, claims directed to chemical compounds and compositions are often rejected over prior art disclosing generic chemical formulae or separate lists of components. The numbers of specific compounds or compositions encompassed by such prior art can be astronomical. The Mylan case provides some tips for arguing over such rejections (preferably without the need to rely on additional experimental results). Possible arguments include identifying the large number of species encompassed by a prior art genus, emphasizing the lack of direction in the prior art toward the specific selections necessary to obtain a claimed compound or composition, and pointing out the difficulty of applying general teachings regarding selection (e.g., of substituents, subcomponents, etc.) to specific compounds or compositions.

Judges: Lourie, Reyna, Stoll