Ex parte Ihn is a recent decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) addressing obviousness and enablement of a claim directed to an organic light-emitting device – particularly to a compound present in the emission layer of the device. Interestingly, the primary reference in the appealed obviousness rejection, Endo, originated from an anonymous third-party submission.

The claim at issue was directed to an organic light-emitting device comprising, inter alia, an emission layer comprising a thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) emitter and a host (two different compounds). The TADF emitter was required to provide particular emission characteristics in use and to have a structure defined by a generic chemical formula.

Endo disclosed specific compounds that were also disclosed in applicant’s specification as TADF emitters. The claim as filed did not require a specific structure for the TADF emitter – merely that the TADF emitter provide the particular emission characteristics. Based on the commonly disclosed compounds, the third-party submitter – and subsequently the examiner – asserted that the claim was unpatentable (identical compounds have identical properties). During prosecution, applicant added the generic chemical formula which excluded the specific compounds disclosed in the primary reference.

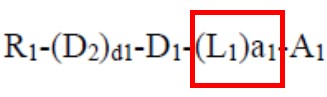

The examiner then took the position that a generic formula in Endo encompassed structures falling within the scope of that amended claim, notwithstanding that no specific compound within the scope of the claim was disclosed in Endo. Applicant countered by arguing that the claim required that a linking group be present between, e.g., an indolocarbazole group and a heteroaromatic group:

“… L1 is selected from: a cyclopentane group, a cyclohexane group… a1 is an integer from 1 to 5…”

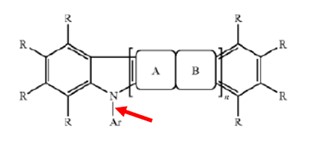

while the structural formula from Endo relied on by the examiner required a single bond:

.

.

While the structural formula from Endo showed connection via a single bond, and most of the exemplary compounds in Endo were connected via a single bond, some exemplary compounds in Endo included an aromatic heterocyclic group indirectly attached to an indolocarbazole skeleton by way of a hydrocarbon group. (This was not inconsistent with the description of Endo’s structural formula, in which polycyclic groups having both aromatic and heteroaromatic rings could be “Ar”).

In view Endo’s disclosure of some compounds in which an aromatic heterocyclic group was indirectly attached, the PTAB found that this “… would have indicated to one of ordinary skill in the art that those structures provide the possibly improved delayed fluorescence emission efficiency and appropriate positional relationship for intermolecular conformation Endo desires from the compounds within…” the structural formula. Thus, the obviousness rejection was affirmed.

With respect to enablement, the examiner argued that the claim covered innumerable combinations of TADF emitters and hosts and that it would have required an undue amount of experimentation to identify combinations of TADF emitters and hosts that provided the claimed emission characteristics. The PTAB declined to adopt the examiner’s reasoning with respect to enablement. The PTAB noted that a large amount of experimentation is not necessarily undue, and the examiner had provided no evidence to support her assertion: “[t]he Examiner’s mere assertions to that effect are insufficient to establish a prima facie case of nonenablement.”

Takeaway: Third-party submissions provide mixed results – sometimes an examiner will rely heavily on the submitted information, and other times it seems that the submitted information has not been carefully considered by the examiner. However, in this case, the third-party submission led to a PTAB finding of unpatentability. This case shows that third-party submissions should not be ignored (particularly in view of their relative low cost) as part of a strategy for influencing the scope of a competitor’s patents.

Compounds are often defined in claims with generic formulae encompassing large numbers of specific compounds. This creates a tension between arguing about what the prior art fairly suggests and arguing about what your own specification fairly enables. It is important to take some care when arguing that prior art does not provide sufficient guidance to lead a skilled artisan to a claimed genus of compounds – particularly if the prior art’s disclosure is not significantly less robust than the disclosure of your own specification.

Judges: Owens, Hastings, Range