Chemical compounds in patent claims often include variables representing different possible substituent groups. For example, a chemical formula may include a variable R1 representing a hydrogen atom or an alkyl group, a variable R2 representing an alkenyl group, and a variable X representing a halogen atom. This notation allows for a compact representation of many different specific compounds (species) within a generic formula (genus).

When evaluating a genus of chemical compounds for obviousness, U.S. examiners often find a disclosed genus of chemical compounds sharing species with the claimed genus. The question then is whether the disclosed genus of chemical compounds is sufficient to render obvious the claimed genus of compounds. This issue is illustrated in the recent Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) case of Ex parte Alig.

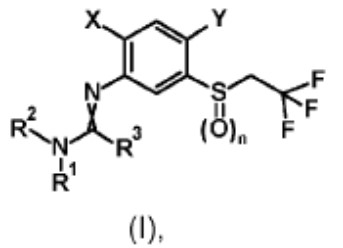

Independent claim 1 recited a method for controlling animal pests with an N-arylamidine substituted trifluoroethyl sulfoxide derivative of formula (I):

where:

n represents the number 1,

X represents fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine,

Y represents (C1-C4)-alkyl or (C1-C4)-haloalkyl,

R2 represents hydrogen, (C1-C4)-alkyl or (C1-C4)-haloalkyl, and

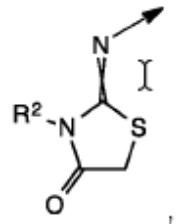

R1 and R3 together with the atoms to which they are attached represent the group

where the arrow points to the remainder of the molecule.

The examiner rejected claim 1 on the ground of non-statutory obviousness-type double patenting over claims 1-20 of U.S. Patent No. 9,642,363 (“the ‘363 patent”) in view of WO 2007/131680. As articulated by the Board, “[t]he Examiner’s position, essentially, [was] that the pending claims would have been obvious over the reference claims because the reference claims disclose a genus of compounds that encompasses the compounds recited in the pending claims.”

The applicant explained that to arrive at the compounds in the pending claims, a person of ordinary skill in the art would need to make several specific choices to narrow the genus recited in the reference claims. For example, the person would need to choose the specific ring structure formed by R1 and R3 in pending claim 1 from among 14 ring systems recited in claim 1 of the ‘363 patent and 16 groups recited in claim 8 of the ‘363 patent. Additionally, the person would need to choose fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine for the variable X in pending claim 1, from among 41 substituents (many of which could contain further substitutions) in the claims of the ‘363 patent. The person also would need to choose (C1-C4)-alkyl or (C1-C4)-haloalkyl for the variable Y in pending claim 1, from among 41 substituents (many of which could contain further substitutions) in the claims of the ‘363 patent. The applicant argued that pending claim 1 was not obvious because the “claims of the ‘363 patent provide no teaching whatsoever that would suggest the specific choices that would lead to the claimed compounds.”

The Board agreed with the applicant. The Board explained that “[t]he fact that the pending claims recite compounds encompassed within the genus disclosed in the prior art is not, by itself, sufficient to establish a prima facie case of obviousness” (citing In re Baird, 16 F.3d 380 (Fed. Cir. 1994) and In re Jones, 958 F.2d 347 (Fed. Cir. 1992)). The Board noted that “[i]n both Baird and Jones, our reviewing court reversed rejections similar to the present rejection, in which the rejected compounds were encompassed by large genera that included millions of compounds, but the prior art did not suggest selecting from those genera the particular compound, or subgenus of compounds, recited in the claims at issue.”

The Board found that the examiner did not “provid[e] a sufficient evidentiary basis explaining why, out of the enormous number of possibilities encompassed within the genus described in the ‘363 patent, a skilled artisan would have made the particular set of selections and modifications that would be required to arrive at the compounds recited in the pending claims.” The Board concluded that “[t]he mere fact that one might arrive at Appellant’s claimed compounds by a hindsight-guided selection of appropriate substituents from the large genus disclosed in the reference claims does not persuade us that the pending claims would have been obvious to a skilled artisan.” Thus, the Board reversed the double patenting rejection.

Takeaway: When claims recite a sub-genus of chemical compounds, and the examiner rejects the claims as obvious over a broader genus of compounds, it is important to analyze the selections necessary to arrive at the sub-genus. If the applied references do not provide guidance for making such selections, then a strong argument can be made against obviousness.

Judges: Fredman, Cotta, Hardman