On July 16, 2020, the Federal Circuit issued a decision in Akeva L.L.C. v. Nike, Inc., Addidas America, Inc. (nonprecedential) in which the difference between removing a subject matter disclaimer from the specification, as opposed to removing one made in amendments and/or remarks during prosecution, amounted to the difference between winning and losing.

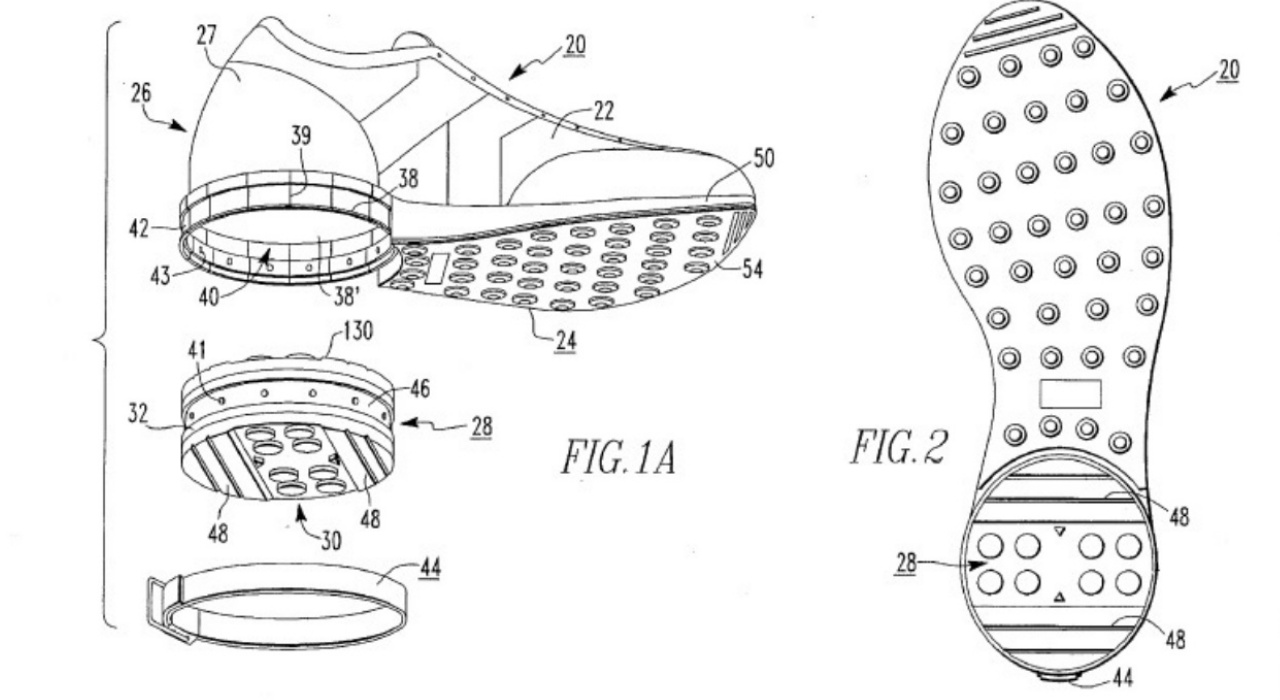

The asserted patents in Akeva are related to advances in athletic shoes and are particularly focused on rear sole (heel) wear and compression. In addressing these problems, Akeva disclosed two improvements: a detachable rear sole that could be replaced or rotated, and a flexible insert. These features provide an athletic shoe with certain wear advantages over shoes with conventional fixed rear soles, and with no insert.

In Akeva multiple related patents were asserted against athletic shoes having conventional fixed rear soles and inserts – an initial patent and several continuations thereof (the continuation patents). Because defendants had sold their shoes in the United States before the filing date of the continuation applications, priority of the continuation applications to the initial patent was critical for patentee’s case.

The continuation patents all claimed priority to the initial patent through the ‘300 patent, which had been separately litigated and found to disclaim conventional fixed rear soles. To address this issue patentee, when filing the continuation applications, amended their specifications to circumvent the disclaimer language in the ‘300 patent specification, and advertised this fact to the Examiner in an Information Disclosure Statement disclosing the previous litigation and by stating their intent to rescind the disclaimer of conventional fixed rear soles. During the litigation patentee took the position that their specification disclaimer, having been rescinded, properly allowed for a priority claim in the continuation applications, through the ‘300 patent, to the initial patent.

The Federal Circuit disagreed. It held that for a claim of priority to be valid there must be a “continuity of disclosure” and “adequate written description support” for the continuation patent claims throughout the entire chain of applications leading back to the initial patent, and that patentee’s amendments to the specifications of the continuation applications were insufficient to rescind the disclaimer in the ‘300 patent. Moreover, patentee’s specification amendments were characterized by the court as likely adding new matter, and they were contrasted with the situation where patentee, in filing a broadened continuation application, disavows a prior disclaimer made in the form of claim amendments and/or remarks in the parent application. See, e.g., Hakim v Cannon Avent Grp., 479 F.3d 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2007) ( “[a]lthough a disclaimer made during prosecution can be rescinded, permitting recapture of the disclaimed scope, the prosecution history must be sufficiently clear to inform the examiner that the previous disclaimer, and the prior art that it was made to avoid, may need to be re-visited.” ).

Takeaway: Amending a specification is always dangerous. In addition to the possibility of adding new matter, the court in this case makes it clear that specification amendments to child cases have no effect on subject matter disclosed or disclaimed in parent cases.

Judges: Newman, O’Malley, Chen

by Richard Treanor

Richard (Rick) L. Treanor, Ph.D., is a founding partner of Element IP. Rick has more than three decades of experience in intellectual property in both the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and private practice. Rick focuses his efforts on the creation, maintenance, and defense of IP rights in proceedings that take place inside the USPTO: patent prosecution, patent appeals, inter partes review, post-grant review, derivation proceedings, covered business method review, re-examination, interference, third party submissions, revival, foreign filing licenses, supplemental examination, etc.