In Ex parte Easson (Appeal 2020-001129), the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) reversed the Examiner’s obviousness rejection because the Examiner failed to show the prior art composition with the required components necessarily had the claimed properties.

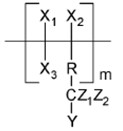

Claim 21 was illustrative and read:

A directly compressible tableting composition, comprising 50-85% by weight of anhydrous calcium hydrogenphosphate, 10-40% by weight of mannitol and 5-20% by weight of sorbitol, wherein said composition has a flow angle in the range of 29 to 33.4° and a bulk density in the range of 0.56 to 0.77 g/ml with a tapped density in the range of 0.73 to 0.92 g/ml.

The Examiner rejected claim 21 as obvious over Yokoi in view of Ranchhordas and Reiff. In particular, the Examiner found that Yokoi taught a powdered composition for tablets that had the same components in overlapping amounts. The Examiner contended that the claimed flow angle range was an inherent property of the claimed composition and thus the composition described in Yokoi must have the same flow angle. The Examiner found that Ranchhordas and Reiff described bulk densities of anhydrous calcium hydrogen phosphate and sorbitol, respectively, both of which overlapped with the claimed bulk density range. The Examiner thus concluded the mixture of the two had the claimed bulk density. Regarding the tapped density range, although the Examiner admitted that the references did not teach the property, he reasoned that “[because] all other properties are overlapping[,] the tapped density would be expected to overlap as well.”

Appellant argued that the Examiner misapplied the law of inherency and that the recited properties were additional limiting requirements of the claimed invention that would not be necessarily possessed by any composition with the recited components. The Board agreed.

In particular, regarding the bulk density, the Board noted that the claimed composition was a mixture of three components and that there was no evidence in the record disclosing the bulk density of mannitol, which was a component other than anhydrous calcium hydrogenphosphate and sorbitol. Also, the Board pointed out that claim 21 encompassed a composition containing as little as 50 wt% of anhydrous calcium hydrogenphosphate, 10 wt% of mannitol, and 5 wt% of sorbitol; that is, the claimed composition could contain as much as 35 wt% of unspecified ingredients with unknown bulk densities. The Board thus concluded that it was not necessarily true that any composition encompassed by claim 21 would have the claimed bulk density.

The Board further found evidence of record that contradicted the Examiner’s inherency conclusion. Specifically, the Board found Appellant’s specification described five compositions containing proportions of anhydrous calcium hydrogenphosphate, mannitol, and sorbitol within the recited ranges; however, two of these compositions had bulk densities and tapped densities that were too high to fall within the specified ranges.

Takeaway: When faced with a composition claim containing property limitations, examiners often assert the properties are inherent if they find a prior art composition satisfying the claimed composition limitations. However, that a property may occur or be present in the prior art is not sufficient to establish inherency. To rely on a theory of inherency, an examiner “must provide a basis in fact and/or technical rationale to reasonably support the determination that the allegedly inherent characteristic necessarily flows from the teachings of the applied prior art.” Ex parte Levy, 17 U.S.P.Q. 2d 1461, 1464 (B.P.A.I. 1990). As illustrated by Easson, an inherency argument lacking such reasoning does not establish a prima facie case of anticipation and/or obviousness, particularly when there is counter evidence showing the properties are additional distinguishing requirements that are not merely results of the composition limitations.

Judges: D. E. Adams, E. B. Grimes, and J. N. Fredman